‘The King of Ballpoint Pens’ Thiên Long: I succeeded because I dared to trust people

https://youtu.be/Mi46u8AeixA?si=FKoW-5CwYZI2npIe

For nearly 45 years, Thiên Long ballpoint pens have become familiar to many generations of Vietnamese people, and are now present in more than 70 countries and territories. That journey began from a very small establishment, founded by Mr. Thọ himself in the early years following the reunification of the country. What fate led him to a product that changed his entire life?

— I’m the eldest of ten siblings, living with our parents and grandmother. After the country reunified, I was only 17 years old. Seeing how hard my parents struggled to feed 13 people and still couldn't make ends meet, I became aware that I had to do something to help the family, so I decided to go out and work.

At that time, not only stationery but also essential goods were in short supply. Every time I passed school gates, I saw people sitting to refill ink and repair pens, attracting many customers. I realized there was a huge demand for pens. Looking into it further, I found out that in Ho Chi Minh City, a few small workshops were already making pens — meaning there was a market, just not yet a professional approach. I asked myself: Why don’t I start selling pens?

I used my small savings and an old, worn-out bicycle as capital. Bearing the responsibility of “elder brother as substitute father,” with very limited capital, I decided to sell pens. At that time, I didn’t think about anything far ahead — it was simply a way to make a living. I went to small workshops to pick up a few dozen pens and sold them retail to newsstands and bookstores.

The job yielded initial results, and I gradually accumulated capital, deciding to switch to manufacturing in 1981 — when I had saved up two chỉ of gold.

— With such a small capital and no production experience, what made you decide to take that leap?

— Back then, I didn’t think about whether I was being reckless or not. I only knew it was something I had to do to make money to support my family of 13.

At first, it was just a family-based economic model, with my siblings and parents, and very few machines. The workshop only did assembly work, since the surrounding Chinese-Vietnamese community had already developed small-scale industries before 1975 and had facilities to produce plastic pen barrels, refills, and pen tips.

Mr. Cô Gia Thọ working on pen production in the early startup days. Photo: Character provided

At that time, the wholesale market was mainly centered in Bình Tây Market and Phùng Hưng Market. As a newcomer without a name, I couldn’t get in. To sell products, I had to "sell on consignment" — meaning I delivered the products first and waited until they were sold to collect payment. With very limited capital, I couldn’t afford to do that. I only had enough money to buy materials for three days of production. Once the pens were made, I pedaled my old bicycle all day, delivering wholesale to newsstands and bookstores. Only by the fourth day, after selling out, could I have enough money to reinvest in materials. I kept going like that, in a rolling fashion.

By 1982, I finally started to enter the wholesale market. A year later, I got married. My wife was naturally business-minded. She used to wholesale soap at the market, which is how we met. Thanks to her help in delivering pens and collecting money, I had more time to focus on production, improving product quality, and developing the manufacturing base.

— In the late 1990s, Thiên Long was one of the first companies to enter Tân Tạo Industrial Park, following the government's call and support. What advantages did this decision bring?

— That was also a matter of fate. My business philosophy has always been: wherever we operate, that place must develop. Even when I only ran a small workshop, I took part in social work, serving as Vice President of the Charity Association in Ward 6, District 6 in the late 1980s. My production organization was also acknowledged by the local authorities, so I was often invited to attend meetings related to reform and small-scale industry.

When Ho Chi Minh City launched a policy to support businesses that committed to hiring more workers, I registered for a VND 200 million interest-free loan and hired 200 more workers. From there, Thiên Long had a solid springboard.

In 1995, the city initiated the founding of Tân Tạo Industrial Park and encouraged businesses to move in for more flexible, regulated, and environmentally friendly production. I believed it was the right direction, so I registered. In 1996, Thiên Long purchased 1.5 hectares of land in Tân Tạo and built a factory. Simultaneously, the city enacted a policy that allowed companies in Tân Tạo to borrow 70% of construction costs from banks — we only needed to provide 30%. This was a great policy, benefiting all three parties: the State could plan production; businesses could invest methodically; banks gained reputable clients.

By the end of 1999 and early 2000, we officially relocated production to Tân Tạo. Previously, our old facility had only about 2,000 square meters, filled with machines. The cramped space limited productivity and specialization. But once we moved into the industrial park, everything changed. We began organizing more professionally, establishing R&D, quality management, wastewater treatment departments… From a small workshop, Thiên Long gradually became a professional enterprise.

Thiên Long’s factory in Tân Tạo Industrial Park (HCMC) from above. Photo: TLG

— Fifty years since the country’s reunification, Ho Chi Minh City has undergone many reforms and economic transformations. For Thiên Long, what did those changes bring or take away?

— Thiên Long is now 44 years old, having witnessed and participated in many policies and mechanisms—from the time the country was in great difficulty to when it developed into one of the leading economies in the region. Initially, we operated as a household business, then evolved into a sole proprietorship. Later, the government called for all small businesses to merge and form a collective group, similar to a cooperative. At that time, there were two pen manufacturing facilities in District 6, so we were grouped together.

In fact, the original intention behind this model was good—it aimed to leverage collective strength. However, at that time, there were no legal regulations regarding capital contribution or branding, so the organization of the collective was incomplete. To legalize the model, we had to create a few pen product lines under a shared brand. But consumers were already familiar with the individual brands of both facilities, so the jointly branded products were not well received. Moreover, grouping businesses in the same industry into one collective meant that individual brands had no motivation to develop—the “merging” was only in form, not in spirit.

After some time, I submitted a petition to withdraw from the collective. Fortunately, the government also recognized the issue and approved the separation and adjustments.

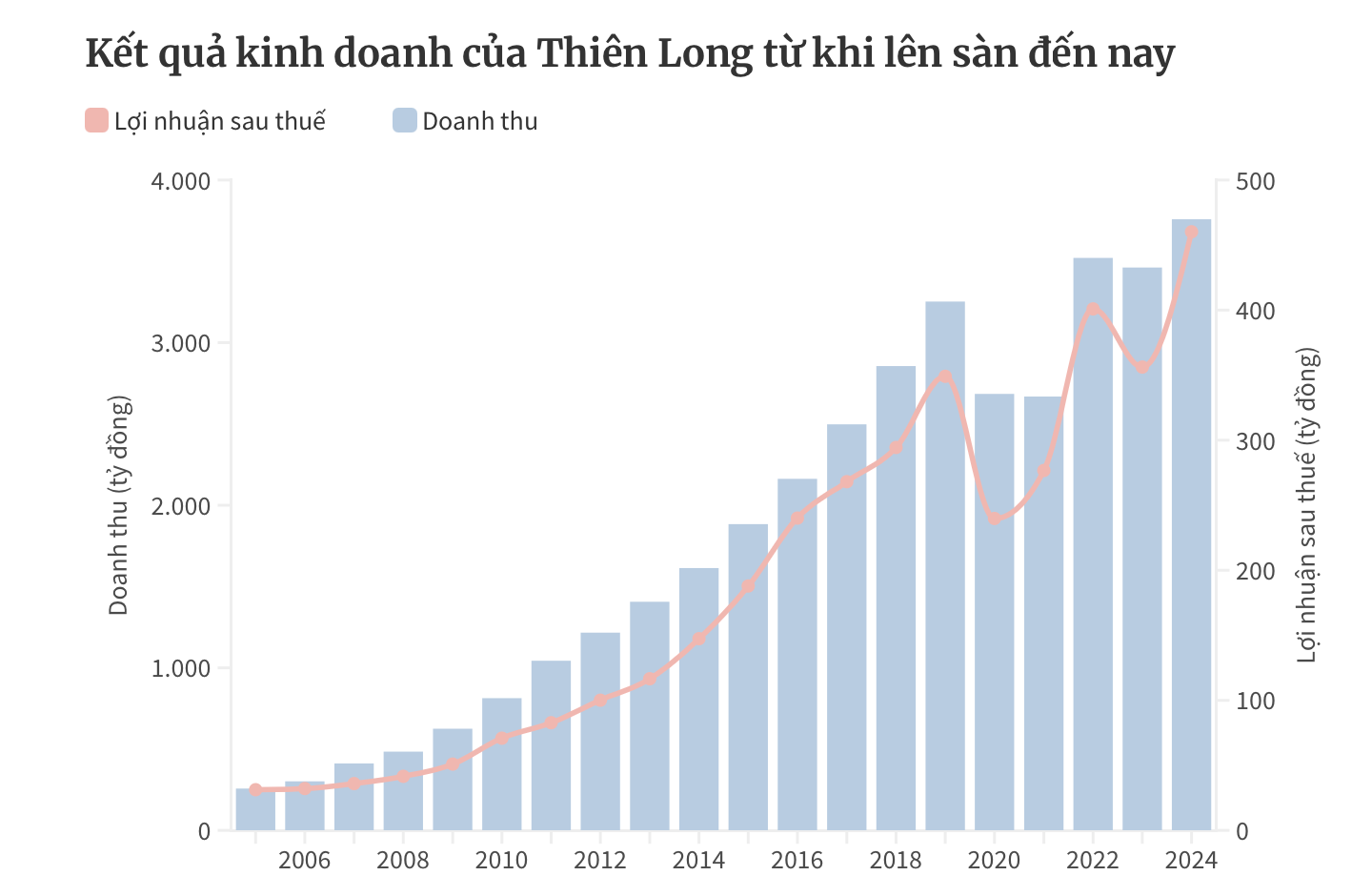

By 1995–1996, Thiên Long had become a limited liability company, then later a public joint stock company, listed on the stock exchange. Thiên Long has gone through many different economic systems and learned a lot from them. Personally, I feel very fortunate to live in a country that is developing day by day. That gives me motivation to grow both myself and the business.

– You have a “4-6” business philosophy, meaning you keep 4 parts for yourself and give 6 parts to others. Could you elaborate more on this philosophy?

– In life, whether in friendships or business dealings, people often seek a balanced 5-5 relationship, where no one gets more than the other. But I believe happiness is the key. I started from zero, and though it was very difficult, I was still cheerful—so getting just 1 or 2 extra parts already felt like happiness to me, let alone receiving 4 parts. People must learn to accept things; if not, no matter how much they have, it will never be enough, and they will still suffer.

This doesn’t just apply to business; I also tend to yield when cooperating with friends or during meetings where we share opinions.

I still remember back in the 1980s, a friend from Long An invited me to join him in collecting watermelons to sell in the city during Tet. At that time, watermelons were only seasonal and not available year-round like today. I agreed to partner with him. Since it wasn’t my area of expertise, I decided to let him take the lead and told him I would accept a smaller share of the profits. Friendships shouldn’t be based solely on benefits; what matters is the connection and the sentiment.

This philosophy and my desire to foster the environment where I work also led Thiên Long to implement CSR programs early on. In my view, only when the surrounding environment develops can one truly be happy. That’s why we always emphasize sharing, supporting, and contributing to overall development. Even though the capacity of each individual or business is limited, Thiên Long focuses its CSR efforts on education, because it is the foundation of a nation’s development. Our CSR activities, in addition to the “Tiếp sức mùa thi” (Exam Support Program) that has run for 23 years, also include support for teachers facing hardships and organizing drawing contests for children.

– You once said: “No matter what you do, you must be able to sleep well at night.” How does this reflect your outlook on life and work?

– I’m the kind of person who values stability and always maintains a certain level of control in everything I do. Before I act or respond to a situation, I always think: Will the other party be satisfied? Is there anything that might upset them? Because of that, I’ve had many sincere friends, reliable partners, and loyal teammates throughout my life. Treating others genuinely and without calculation allows me to sleep soundly every night.

This principle also guides me in business. Thiên Long is a joint stock company, and I’m responsible to our shareholders. That means I must ensure they can rest easy, knowing they are investing in a financially sustainable company with a transparent system that avoids unnecessary risks.

At the same time, I believe that living truthfully is always the best way. Whatever I think or do, I say exactly that. Between people, sincerity is what matters most. With those I feel close to and respect, I’m even more honest.

To live truthfully, I see myself as an open book. I’m always willing to listen to feedback—even from employees—about where I may be wrong, where I may be lacking, or where I need improvement. I’m not afraid to share my shortcomings so that I can receive guidance and advice from those with expertise.

– After over 40 years of development, Thiên Long continues to innovate and hasn’t become stagnant. What’s your secret, and how have you maintained a spirit of learning within the company all these years?

– The secret lies in learning. I’ve always believed that a learning mindset is crucial to avoid becoming obsolete. I’ve spread this spirit throughout the company by trusting and encouraging everyone to keep learning and improving each day. I send employees to training, create an open environment for them to express new ideas. I believe that trust is the most fundamental element for building strong relationships, and from there, my team can confidently be creative and contribute to the company’s growth.

Everyone can learn—but what’s important is daring to trust and act on it. I’m someone who chooses to trust others first—be it teammates, employees, friends, or business partners.

In the early days of building Thiên Long, I worked closely with many suppliers of materials and machinery. I openly admitted that our company didn’t know much and asked them to guide us, while also requesting the materials we needed. That’s how I placed my trust in our partners. As a result, my team and I learned a great deal. I was never afraid that showing our weaknesses would make us vulnerable or manipulated. Because when you trust someone first, they can feel your sincerity—and from there, they’ll genuinely support you and grow with you.

– In the early stages of building the company, I understood that I didn’t have technical expertise, so I had to find a mold engineering specialist to invite for collaboration. I also frankly told the first mold engineer of Thiên Long that I wasn’t very knowledgeable in technical matters.

After recognizing and confronting the issue directly, I chose to trust professionals and let them take charge instead of stubbornly trying to control everything myself. I trusted them and gave them the space to showcase their strengths, and thanks to that, Thiên Long made many technical advancements and is now capable of mastering its own technology.

Through several decades, I’ve realized that the failures that resulted from trusting others were insignificant compared to the successes that trust has brought. Of course, trust must not be blind; it must be guided by rational judgment.

– In your role as a father, what principles do you follow in educating your children about career and life?

I teach my children to nurture heart – talent – virtue. If you have talent, you must also have heart and virtue. I believe that heart and virtue are the core values of being a good human, while talent is something essential—but at times, it can only be applied in a specific field. My children have had far better learning conditions than I ever did, so their talents surpass mine. If they also cultivate heart and virtue, their chances of success will be very high. The philosophy of heart – talent – virtue is a beautiful tradition and legacy of the Vietnamese people, and I have always studied and strived to follow it.

This philosophy is the greatest legacy and life baggage I can pass down to my children. To me, material wealth may be lost one day for various reasons. But heart – talent – virtue will endure over time. When my children possess all three elements, they will be loved and appreciated by others, allowing them to build a strong network of relationships—and from there, many great opportunities will come their way. Ultimately, whether in business or in building a career, it’s all part of the journey of becoming a good person.

– How are you preparing the next generation of leadership for Thiên Long?

Thiên Long has operated with a standardized system from the very beginning. Even back in the 1990s, when we were just a small manufacturing facility, I wasn’t directly managing everything. In 1993, I even went to Taiwan (China) to study and conduct research, because we already had a management team in place at home. To this day, the entire company is run by professionals. Thanks to these standardized processes, I can feel at ease, and the company can operate in a well-structured, complete manner.

A business doesn’t always function best when the owner tries to control everything. Every department at Thiên Long is given full authority within its scope of responsibility. And within Thiên Long’s system, each department prepares a successor—its own “seed” for the future.